Hidden Records: St. Louis

The Lost City of the Mounds

12/31/20252 min read

Hidden Records: St. Louis — The Lost City of the Mounds

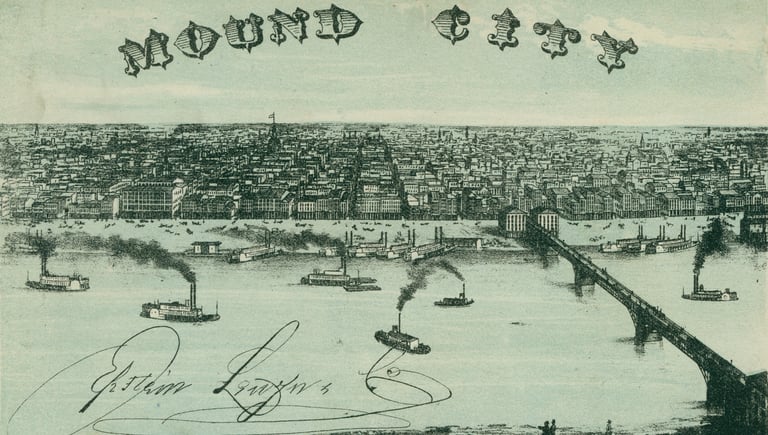

Before it became St. Louis, the area was widely known in the 18th and early 19th centuries as Mound City. Early explorers, surveyors, and settlers documented dozens of large earthen mounds spread across what is now downtown St. Louis and its surrounding neighborhoods. These mounds were not random heaps of soil; they were carefully constructed ceremonial, burial, and civic structures created by Indigenous peoples connected to the greater Mississippian cultural world.

St. Louis was part of a vast Indigenous urban corridor aligned along the Mississippi River, directly across from Cahokia Mounds, the largest known pre-contact city north of Mexico. Together, these sites formed an interconnected system of governance, trade, ceremony, and astronomy. The Mississippi River functioned as a central artery, not a boundary, linking communities for hundreds of miles.

By the early 1800s, St. Louis contained more than 25 prominent mounds, some reaching over 30 feet high. One of the largest, known as the “Big Mound,” stood near present-day Broadway and Mound Street. These earthworks were well known and widely referenced in early city records. However, as the city expanded, the mounds were systematically removed.

Between the mid-1800s and early 1900s, nearly all of St. Louis’s mounds were destroyed. They were leveled to make way for railroads, roads, warehouses, brickmaking, and urban development. Soil from the mounds was often sold or reused as fill. This destruction occurred before modern archaeological protections existed, and much of the material was never studied or documented.

The erasure of the mounds coincided with a broader cultural narrative that minimized Indigenous engineering and urban planning. Rather than preserving the earthworks as evidence of a sophisticated pre-existing city, development was prioritized. By the early 20th century, St. Louis’s identity as “Mound City” had largely vanished from public memory.

Today, only written accounts, maps, and scattered artifacts testify to the scale of what once stood. Beneath streets, buildings, and infrastructure, the original landscape remains layered below the modern city. St. Louis did not rise from empty land—it was built atop an ancient Indigenous metropolis.

The hidden record of St. Louis challenges long-held assumptions about North American history. It reveals that complex cities, regional planning, and monumental architecture existed here long before European settlement. Recognizing this truth is not about rewriting history—it is about restoring what was intentionally forgotten.